The projective roles of the architectural drawing in the discipline of architecture are simultaneously exhilarating and daunting. The formal predilections of Modernism, frequent shifts in cultural paradigms, the displacement of manual drawing by keyboard procedures, and the increasing links between software applications and material fabrication processes suggest a reassessment of the role of drawing.

These working notes are an attempt to broaden considerations surrounding the drawing through the cultivation of its various levels of communication, the stimulation of its latent content, and the catalyzing of its speculative roles. These thoughts are an attempt to augment the homogeneous and reductive practices of drawing and to reestablish its imaginative, generative, and creative agencies.

To overcome the legacy of reductive representational practices, we should conceptualize the construction of drawing as more than a tool for problem solving, organization, or expression. A number of interesting questions deserve reconsideration: the distance between the architect, the drawing, and construction; the differences between varied drawing types and their vested authorities; the debates over white page versus black screen; the temporality of drawing and its reminiscent and speculative potentials; and the dimensions of experience that perpetually elude the conventions of drawing. While not at the forefront of educational or professional discussions, engaging the spirit of these questions might allow the architectural drawing to reassert its formidable creative agency, while participating in the continuities of cultural imagination.

Motivated by ideas and language on the one hand and by geometry and material projection on the other, the architectural drawing has undergone a multitude of developments, interpretations, and transformations. It has defined and been defined by complex cultural circumstances. In my own work and my work with students, I am interested in the drawing’s capacity to represent these complex situations. I am optimistic about the conceptual and speculative potential of mark-making, valuing what is known as well as the accidental and unborn; the margins and figures count alike.

Unlike more exclusionary positions, my work employs multiple representational techniques simultaneously, allowing the drawing to communicate on several levels. The use of indexical sets, notation, diagrammatic assemblies, material indications, language, and other generative marks cultivates latent relations, facilitating the drawing’s investigative potential. Manual, digital, and hybrid techniques are all possible. Local “ecologies of potential” emerge from this choreography, teasing out spatial possibilities from the drawings.

The avoidance of premature ideational, geometric, and material reduction is one of the primary ambitions of my work, and a necessary ingredient in the imaginative life of the drawing. The act of drawing itself becomes a form of discovery of the logics and structure of the work.

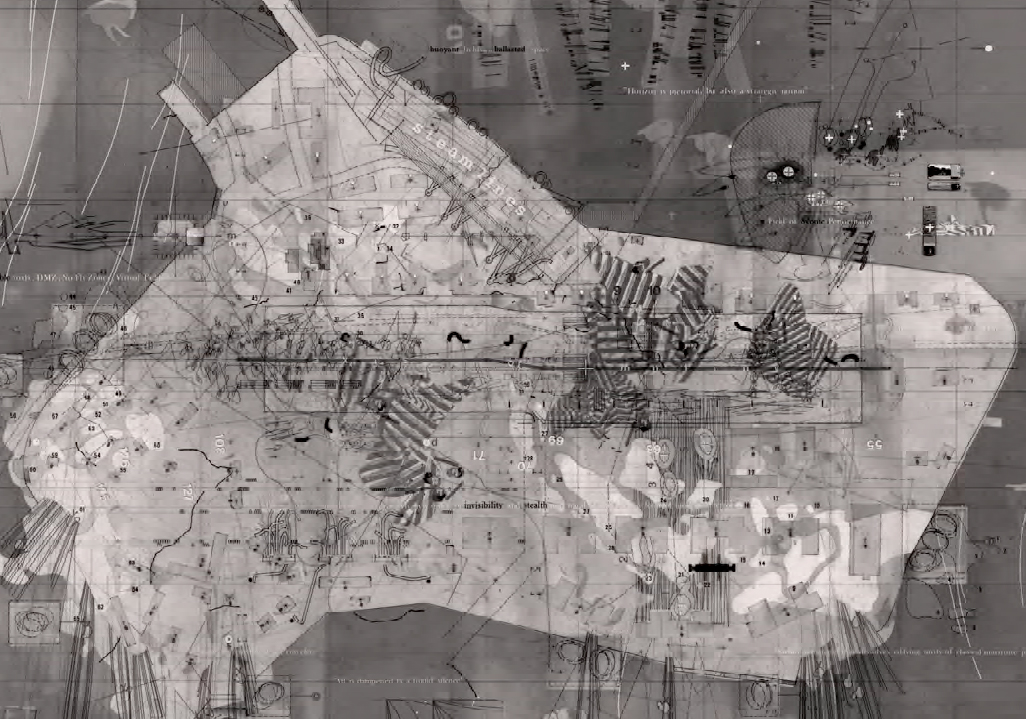

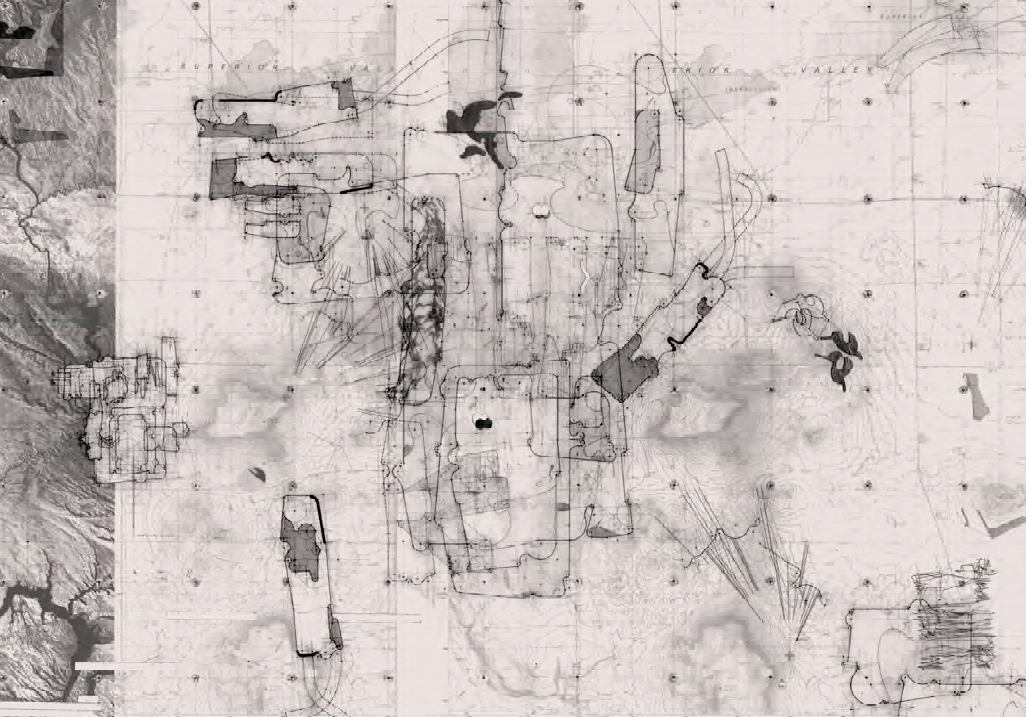

In the Strategic Plot for the David’s Island Competition, for example, speculations about content and programmatic structure emerge from a number of sources, not the least of which is the imagined potential in the space of the Plot itself. Like a game board or a map, it occupies a representational territory between landscape and architecture, incorporating notations for future development. Material configurations coalesce with diagrammatic and durational marks, opening representational borders and cultivating more fluid ideological, material, and temporal assemblies.

In the Fast Twitch drawing, I set out to explore desert occupations linked to ground, sky, and horizon. This drawing includes territorial marking, notation, language, and material indications. As it developed, my interests expanded to include hybrid archetypes, subtle shifts in perceptual awareness, incompleteness, and relations between rhetorical structuring and embodied experience. The drawing examines these interests through varied communicative levels, opening analogical and intuitive means towards the generation of a proposal for desert occupation. Conventional drawing types intermingle with other invented representational techniques, enabling the emergence and eventual synthesis of a range of ideas, with material and spatial ramifications nearly impossible through more traditional drawings.

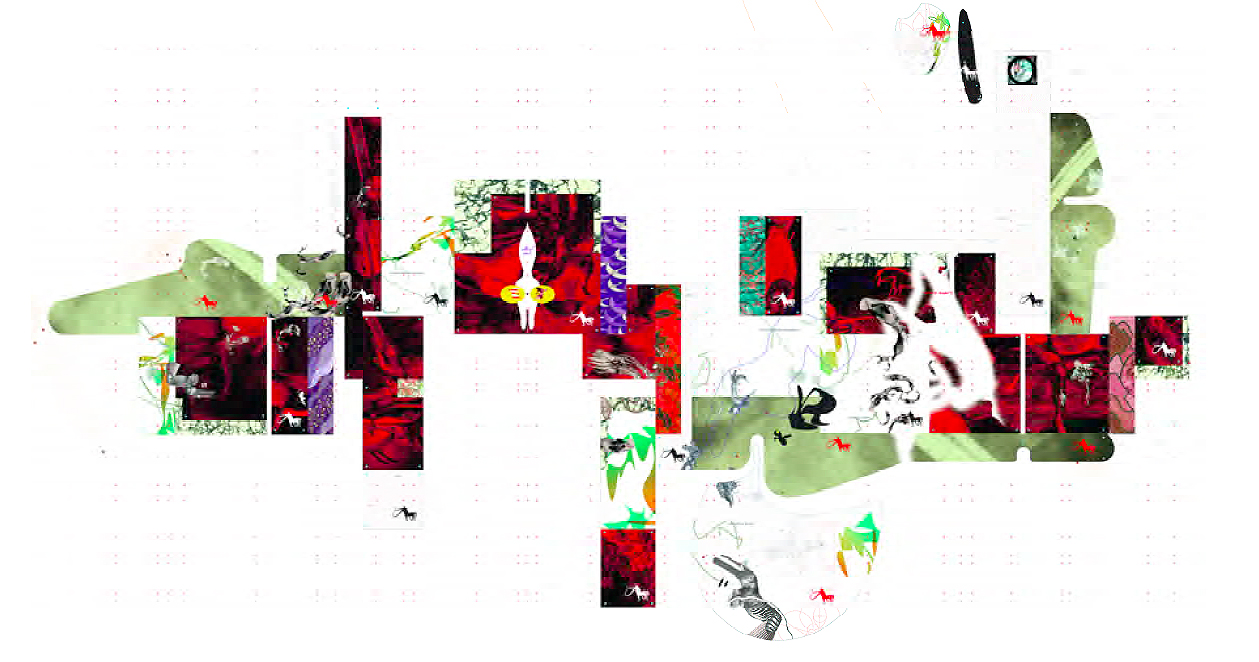

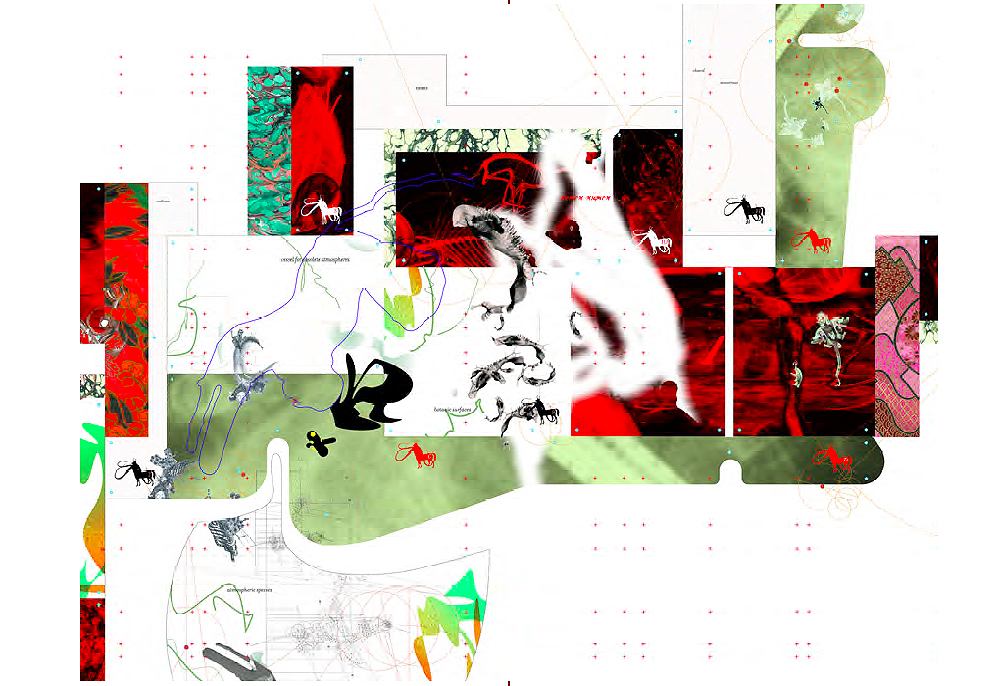

The Metaspheric Zoo (a cross between “metaphor” and “atmosphere”) is a speculative proposal for the Prague Biennale. It is the first in a series of preparatory drawings to discover and theorize the zoo. Its primary topical, relational, and programmatic attitudes were established through an image combining characteristics of a puzzle, a geographic matrix, and a taxonomic inventory. Ambient surfaces tease coded and indexical marks. Instrumental practices are crossed with language and invented “characters” toward the creation of a synthetic, incomplete, and strangely familiar whole. From this beginning, programmatic interests in botanic surfacing, a roving taxidermy, and a vessel for obsolete atmospheres emerge, confronting the disparate impulses of instinct and desire which are all but eradicated from our over-programmed society.

Although culturally grounded, drawing is a kind of personal cartography in which circumstance and creative identity coalesce toward spatial configurations. Drawing is a risk, and confronting the white surface, or black screen, is an act of violation. It is an assault on whiteness and abstraction.

By engaging varied and shifting levels of communication (in many ways analogous to our embodied experience of space), the speculative, imaginative, and latent capacities of drawing may make it possible to forget, momentarily, the scenic surface of the image. The possibility of seeing behind, beneath, and through the space of drawing—and the drawing of space—toward greater cultural agency and communicative range is the promise and provocation of architectural representation. Though the parameters have radically changed, the architectural drawing remains an unfinished and tantalizing project.

Author Perry Kulper is an architect and SCI-Arc Faculty member living in Los Angeles.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2005 in arcCA 05.3, “Drawn Out.”