The AIACC 25-Year Award honors distinguished California architecture of enduring significance. This award recognizes a project completed 25 to 50 years ago that has retained its central form and character with the architectural integrity of the project intact.

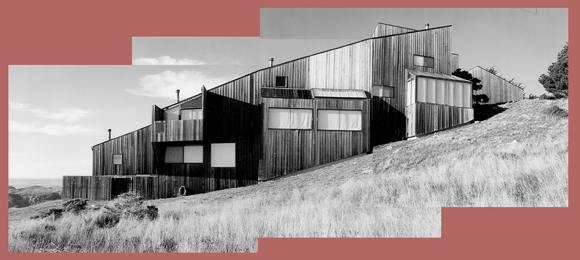

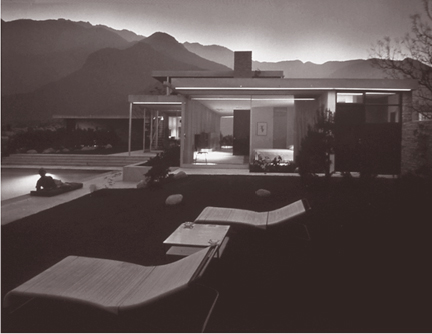

Since it became a formal part of the AIACC awards program in 1989, the 25-Year Award has been given to California buildings of lasting design distinction. Modeled on the national AIA’s award of the same name, it recognizes those structures that have continually influenced contemporary practice. Since the award’s inception, the Council has recognized fifteen buildings. Among these are many buildings well known by architects here and across the country. Richard Neutra’s Kauffmann House in Palm Springs, Pierre Koenig’s iconic Case Study House #21, Sea Ranch Condominium One by MLTW, and the Eames House are all past 25-Year Award winners.

The absence of an award this year troubled the jury. We were concerned that it sends the message that there are no buildings in California worthy of recognition, which is clearly not the case. Unfortunately, we were presented with only three submissions, and, while each was a distinguished, well-designed building, none were perceived to have had broad and lasting influence. Each represented advances in particular areas, but none rose to the kind of touchstone status so notable in past recipients—none were as influential as the Eames House, for instance.

Perhaps some will feel that this is too high a standard, but the jury felt that many important California buildings that meet the standard were simply not on the table. We discussed at length how the profession could rectify this situation. How can we encourage the profession to take up the task of documenting our past achievements? After all, if we don’t lift up the most important work of our profession, who will?

The most straightforward way to get more submissions is to encourage the original designers to submit their work. Friends and colleagues of designers of important buildings should urge them to gather the necessary materials and submit. Offer to lend assistance if necessary. In many cases, the original designers are no longer practicing, but the archives are still available. Sometimes all these designers need is a little encouragement.

While it would be ideal to have the original designers submit their buildings, it is not always possible. Yet the profession needs to assure that its lasting legacy is recognized. We need to be reminded of the lessons of these places, and we need to communicate their appreciation to the public. The jury suggests that there are two other professional advocates available: local AIA chapters and architecture schools.

Local chapters are repositories of the histories and stories of all that is built within their boundaries. As any active member knows, the collective memory present in any chapter is a resource of great value. Additionally, local chapters are the best advocates for their region. The trick is to tap into this wealth of information. Presently, the AIACC has assembled a Recognition Task Force, whose job it is to forward nominations to the Council for various achievement awards and other statewide recognition. While this process is designed to turn up people worthy of recognition, perhaps the mechanism is in place to add nominations of buildings for the 25-Year Award. Local chapters could poll their members annually on local structures of significance and could organize a committee to gather the materials necessary for a submission.

Schools of architecture are the other institution equipped to research and document buildings. Many schools are already participating in case study programs, and every school teaches architectural history. Students and the profession would each benefit from the effort required to generate a submission binder. Schools can give students credit as a directed study or as part of coursework in history, theory, or studio classes. This process might be akin to the long California elementary school tradition of building models of California’s missions.

Finally, the AIACC should be annually scanning its databases of past award recipients and forwarding this information to the Design Awards Committee and to the local chapters. Perhaps through such collective efforts we can document and recognize these important and influential California buildings.

Author Eric Naslund, FAIA, is a principal at Studio E Architects in San Diego. He is the past chair of the AIACC Design Awards Program and currently serves on the editorial board of arcCA. He is an adjunct faculty member at Woodbury University in San Diego and will be the Kea Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Maryland this Fall. Eric served on this year’s AIACC Design Awards jury.

Originally published 3rd quarter 2004 in arcCA 04.3, “Photo Finish.”